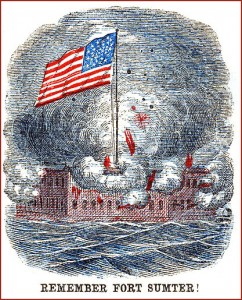

The following article, edited by Frank Moore, was published to honor the fiftieth anniversary of the bombardment and fall of Fort Sumter.

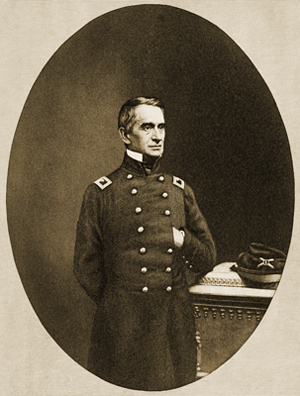

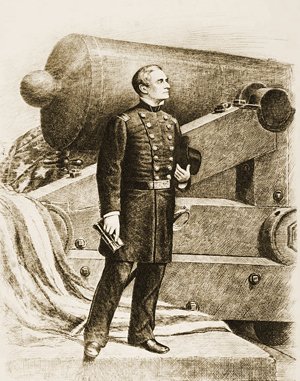

In the history of the Southern conspiracy, General Robert Anderson must hold a distinguished place, being the first federal officer against whom the fatal thought of rebellion took voice in the throat of a cannon; and though his shattered health has constrained him to play no further part in the tragedy which he opened with such brilliancy, his loyalty to “Old Glory,” his wise courage and Christian firmness, in that hour of peril, will ever keep his name honored and revered among the American people.

General Anderson came from a patriotic and military family. His father, Captain Richard C. Anderson, was the man whose little band surprised an outpost of the Hessians at Trenton, on the night prior to the decisive battle of that place—an attack which the Hessian commander, Colonel Rahl, then on the lookout for Washington, construed to be the whole assault against which he had been warned. General Washington met Anderson retreating with his Company, and was very indignant at what they had done, fearing it would prepare the enemy for their advance in force. The result, however, proved the contrary, and Anderson was then complimented on the exploit. Captain Anderson served with Washington throughout the New Jersey campaign.

The subject of this sketch–Robert Anderson–is a native of the state of Kentucky. The blood of a brave soldier ran in his veins and displayed itself in his early desire to adopt the profession of arms. Passing over young Anderson’s preliminary studies and scholastic successes, we find him, in 1832, acting Inspector General of Illinois Volunteers in the Black Hawk War. He filled this situation with credit to himself, from May until the ensuing October. In the following June 1833, he was made First Lieutenant. From 1835 to 1837 he occupied the responsible post of Assistant Instructor and Inspector at the United States Military Academy. He was assigned to the staff of General Winfield Scott as aide-de-camp in 1838, and in 1839 published his Instructions for Field Artillery, Horse and Foot, arranged for the Service of the United States—a hand-book of great practical value.

Lieutenant Anderson’s service during the Indian troubles was acknowledged by a brevet captaincy, April 2, 1838. In July of the same year, he was made Assistant Adjutant General with the rank of Captain, which he subsequently relinquished on being promoted to a captaincy in his own regiment, the Third Artillery.

In March 1847, he was with his Regiment in the Army of General Scott, and took part in the battle of Vera Cruz; being one of the officers to whom was entrusted, by Colonel Bankhead, the command of the batteries. This duty he accomplished with signal skill and gallantry. He remained with the Army until its triumphant entry into the Mexican Capital the following September.

During the operations in the valley of Mexico, Captain Anderson was attached to the brigade of General Garland which formed a portion of General Worth’s Division. In the attack on El Molino del Rey, September 8, Anderson was severely wounded. His admirable conduct under the circumstances was the theme of praise on the part of his men and superior officers. Captain Burke, his immediate commander, in his dispatch of September 9, said: “Captain Robert Anderson (acting field officer) behaved with great heroism on this occasion. Even after receiving a severe and painful wound, he continued at the head of the column, regardless of pain and self-preservation, and setting a handsome example to his men of coolness, energy and courage.” General Garland speaks of him as being “with some few others the very first to enter the strong position of El Molino;” and adds that “Brevet Major Buchanan, Fourth Infantry, Captain Robert Anderson, Third Artillery, and Lieutenant Sedgwick, Second Artillery, appear to have been particularly distinguished for their gallant defense of the captured works.” In addition to this testimony, General Worth directed the attention of the Secretary of War to the part Anderson had taken in the action. He was made Brevet Major, his commission dating from the day of the battle.

In the year 1851, he was promoted to the full rank of Major in the First Artillery. It was while holding this rank and in command of the Garrison of Fort Moultrie, that the storm which has so devastated this fair land first gathered strength and broke upon us.

On the 20th day of December 1860, the state of South Carolina declared itself out of the Union. The event was celebrated in numerous Southern towns and cities by the firing of salutes, military parades, and secession speeches. At New Orleans a bust of Calhoun was exhibited, decorated with a cockade, and at Memphis the citizens burned Senator Andrew Johnson in effigy. The plague of disloyalty overspread the entire South. In the meantime, while the commissioners from South Carolina and the plotting members of Congress from the Border States were complicating matters with a timid and vacillating President Buchanan, Major Anderson found himself with less than one hundred men, shut up in an untenable fort, his own government fearing to send him reinforcements. Cut off from aid or supplies, menaced on every side, the deep murmurs of war growing louder and more threatening, the position of Major Anderson and his handful of men became imminent in the extreme. At this juncture of affairs, the brave soldier gave us an illustration of his forethought and sagacity.

One sunny morning crowds of anxious people fringed the wharves of Charleston, watching the mysterious curls of smoke that rose lazily from the ramparts of Fort Moultrie, and floated off seaward—smoke from the burning gun-carriages.

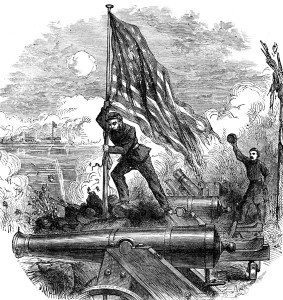

On the night previous, Major Anderson had quietly removed his men and stores to Fort Sumter, the strongest of the Charleston fortifications, and the key of its defenses. The deserted guns of Moultrie were spiked and the carriages burned to cinders. The evacuation of the fort commenced a little after sunset. The men were ordered to hold themselves in readiness, with their knapsacks packed, at a second’s notice; but up to the moment of their leaving they had no idea of abandoning the post. They were reviewed on parade, and then ordered to two schooners lying in the vicinity. The garrison flag unwound itself to the morning over Sumter.

The rage of the South at this unexpected strategic maneuver was equaled in its intenseness only by the thrill of joy that ran through the North. Major Anderson and his command were safe, for the time being, and treason disconcerted.

“Major Robert Anderson,” said the Charleston Courier, bitterly, “has achieved the unenviable distinction of opening civil war between American citizens by an act of gross breach of faith.”

The sequel proved his prudence. Having all the forts of the Harbor under his charge, he had, necessarily, the right to occupy whatever post he deemed expedient. He did his duty, and he did it well. His course was sustained in the House of Representatives, January 7, 1861. Before the first burst of indignation had subsided, Fort Moultrie was taken possession of by the South Carolinians, and carefully put into a state of defense. The rebel convention ordered immense fortifications to be built in and about Charleston Harbor, to resist any reinforcements that might be sent to Major Anderson. Strong redoubts were thrown up on Morris and James Islands, and Fort Moultrie, Johnson and Castle Pinckney, stood ready to belch flame and iron on the devoted little garrison. Sumter was invested; no ship could approach the place in the teeth of those sullen batteries.

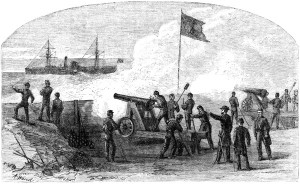

On the 8th of April, information having been given by the United States Government to the authorities of Charleston that they desired to send supplies to Fort Sumter on an unarmed transport, they were informed that the vessel would be fired upon and not allowed to enter the port. The United States Government then officially advised the insurgents that supplies would be sent to Major Anderson, peaceably if possible, otherwise by force. Lieutenant Talbot, attached to the Garrison at Fort Sumter, and bearer of this dispatch, was not permitted to proceed to his post. The steamer Star of the West was signaled at the entrance of the harbor on the morning of the 9th. She displayed the United States Flag, but was fired into repeatedly from Morris Island’s battery. Her course was then altered, and she again put out to sea.

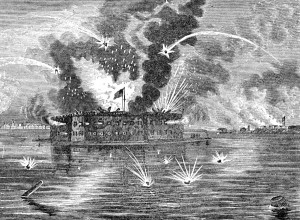

The formidable floating battery, constructed and manned at Charleston, was taken out of dock on the evening of the 10th and anchored in a cove near Sullivan’s Island. About seven thousand troops now crowded the earthworks and forts under command of General G.T. Beauregard. The report that a fleet lay off the bay, waiting for a favorable tide to enter the harbor and relieve the fort, caused the greatest excitement in Charleston.

On the afternoon of April 11, Colonel Chestnut and Major Lee, aids to General Beauregard, conveyed to Fort Sumter the demand that Major Anderson should evacuate that fort. Major Anderson refused to accede to the demand. On being waited on by a second deputation (April 2, 1:00 a.m.) desiring him to state what time he would evacuate, and to stipulate not to fire upon the batteries in the meantime, Major Anderson replied that he would evacuate at the noon of the 15th if not previously otherwise ordered, or not supplied, and that he would not in the meantime open his fire unless compelled by some hostile act against his fort or the Flag of his Government.

At 3:30 a.m. the officers who received this answer notified Major Anderson that the batteries under command of General Beauregard would open on Fort Sumter in one hour, and immediately left. The sentinels on Sumter were then ordered in from the parapets, the posterns closed, and the men directed not to leave the bomb-proofs until summoned by the drum. The Garrison had but two days’ rations.

At 4:30 Friday morning, fire was opened upon Fort Sumter from Fort Moultrie, and soon after from the batteries on Mount Pleasant and Cummings Point, then from an unsuspected masked battery of heavy columbiads on Sullivan’s Island. It soon became evident that no part of the beleaguered fort was without the range of the enemy’s guns. A rim of scarlet fire encircled it. Meanwhile the undaunted little band of seventy true men, took breakfast quietly at the regular hour, reserving their fire until 7:00 a.m., when they opened their lower tier of guns upon Fort Moultrie; the iron battery on Cummings’s Point, the two works on Sullivan’s Island and the floating battery, simultaneously.

When the first relief went to work, the enthusiasm of the men was so great that the second and third reliefs could not be kept from the guns. The rebel iron battery was of immense strength, and our balls glanced from it like hail-stones. Fort Moultrie, however, stood the cannonading badly, a great many of our shells taking effect in the embrasures. Shells from every part burst against the various walls of Sumter, and the fire upon the parapet became so terrific that Major Anderson refused to allow the men to work the barbette guns. There were no cartridge bags, and the men were set to making them out of shirts. Fire broke out in the barracks three times and was extinguished. Meals were served at the guns. At 6:00 p.m. the fire from Sumter ceased. Fire was kept up by the enemy during the night, at intervals of twenty-five minutes.

At daybreak the following morning the bombardment recommenced. Fort Sumter resumed operations at 7:00 a.m. An hour afterward the officers’ quarters took fire from a shell, and it was necessary to detach nearly all the men from the guns to stop the conflagration. Shells from Moultrie and Morris Islands now fell faster than ever. The effect of the enemy’s shot, on the officers’ quarters in particular, was terrible. One tower was so completely demolished that not one brick was left standing upon another. The main gates were blown away, and the walls considerably weakened. Fearful that they might crack, and a shell pierce the magazine, ninety-six barrels of powder were emptied into the sea.

Finally the magazine had to be closed; the material for cartridges was exhausted, and the garrison was left destitute of any means to continue the contest. The men had eaten the last biscuit thirty-six hours before. They were nearly stifled by the dense, livid smoke from the burning building, lying prostrate on the ground with wet handkerchiefs over their mouths and eyes. The crashing of the shot, the bursting of the shells, the falling of the masonry, and the mad roaring of the flames, made a pandemonium of the place. Strangely enough but four men had been injured, thus far, and those only slightly.

Toward the close of the day, ex-Senator Wigfall suddenly made his appearance at an embrasure with a white handkerchief on the point of a sword and begged to see Major Anderson, asserting that he came from General Beauregard.

“Well sir!” said Major Anderson, confronting him. General Wigfall, in an excited manner then demanded to know on what terms Major Anderson would evacuate the post. The Major informed him that General Beauregard was already advised of the terms.

“Then, sir,” said Wigfall, “the Fort is ours.”

“On those conditions,” replied Major Anderson. During this interview the firing from Moultrie and Sullivan’s Island had not ceased, though General Wigfall timidly displayed a white flag at an embrasure facing the batteries. Wigfall retired.

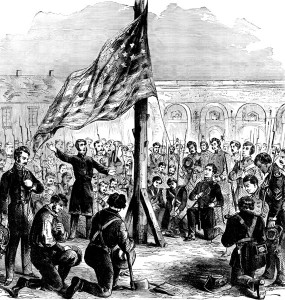

A short time afterward a deputation consisting of Senator Chesnut, Roger A. Pryor, and two others, came from General Beauregard, and had an interview with Major Anderson. It then turned out that the officious Wigfall had “acted on his own hook,” without any authority whatever from his commanding General. After a protracted consultation and a second deputation, Major Anderson agreed to evacuate Fort Sumter the next day. This was Saturday evening. That night the garrison took what rest it could. Next morning the Isabel anchored near the fort to receive the gallant little band. The terms of evacuation were that the garrison should take of its individual and company property; that they should march out with their side and other arms with all the honors, in their own way, and at their own time; that they should salute their Flag and take it with them.

With their tattered flag flying and the band playing national airs, these seventy heroes marched out of Fort Sumter. Seventy to seven thousand!

Major Anderson’s heroic conduct had drawn all loyal hearts toward him, and it was the wish of the country that he should immediately be invested with some important command. He was made a Brigadier General and sent to Kentucky to superintend the raising of troops in that state. But the terrible ordeal through which he had just passed and the results of hardships undergone in Mexico, unfitted him for active duty. Since then, General Anderson has resided in New York City. A tall, elderly gentleman in undress uniform, leading a little child by the hand, is often seen passing slowly along Broadway. His fine, intellectual face is the index to the genuine goodness and nobility of his heart. Though men of noisier name meet you at each corner, your eyes follow pleasantly after this one—Robert Anderson.

![]() Be sure to visit U.S. History Images to see more images of the Fort Sumter Battle.

Be sure to visit U.S. History Images to see more images of the Fort Sumter Battle.

Source:

Moore, Frank, ed. “The Fall of Fort Sumter: Heroes and Martyrs.” Fort Sumter Memorial. New York: Edwin C. Hill, 1915. 17-30. Print.

Want to learn more about the Battle of Fort Sumter and the Start of the Civil War? Check out my new Kindle ebook on Amazon!